Examine the canon.

About a month ago Leslie asked me to put together a reading list of important genre works for her students. So, based on my own experience, I came up with the following list of important genre novels, collections, and critical works. I hope that it might serve as a resource to any of my readers unfamiliar with genre fiction, or with those who are looking to explore any classics they may have missed.

Naturally, this list is far from authoritative. If I've missed any critical works (and there's little doubt I have), please feel free to make a note in the comments section.

Non-Fiction

The following books examine the history, meaning and impact of SF lit:

Trillion Year Spree: The History of Science Fiction, by Brian Aldiss with David Wingrove

The World Beyond the Hill: Science Fiction and the Quest for Transcendence by Alexei and Cory Panshin

The Dreams Our Stuff is Made Of: How Science Fiction Conquered the World, by Thomas M. Disch

Each of these comprehensive works has plenty of value for anyone interested in taking a deeper look at SF's roots. These are academic texts, but quite readable and interesting.

Fiction

Here's a list of what I consider the most important books in the science fiction genre, in roughly chronological order:

Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley. The earliest story that could be considered "true" SF, with its focus on the possible consequences of scientific progress. The creature's creation is explicitly linked to science, not magic, an important distinction between SF and Fantasy lit.

The War of the Worlds and The Time Machine, both by H.G. Wells. The first alien invasion story, the first time travel story, which became subgenres within SF.

Journey to the Centre of the Earth and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne. Prototypical stories about exploring new worlds, though in this case they lie hidden on our own world. Leagues is most famous for introducing Captain Nemo and his amazing submarine, the Nautilus.

I would describe Shelley, Wells and Verne as the European grandparents of an essentially American art form (in spirit, if not always in fact). So let’s get into the first important American authors…

A Princess of Mars, The Gods of Mars, The Warlord of Mars, all by Edgar Rice Burroughs. There are 11 novels in Burroughs’ “John Carter of Mars” series, but these three will serve as an introduction to another subgenre within SF, the high adventure story, rife with many of the features that would later become SF stereotypes: ray guns, gorgeous, scantily clad alien women, hypermasculine heroes, exotic aircraft, and a solid dose of plausible-sounding science to make the whole thing work. I’ll save mention of Burroughs’ most famous creation, Tarzan, for the fantasy section.

Foundation, Foundation and Earth, and Second Foundation by Isaac Asimov. Asimov is one of three recognized giants of SF, along with Arthur C. Clarke and Robert Heinlein. These novels lay the foundation (if you’ll forgive me) for another subgenre, that revolving around intergalactic empires.

I, Robot by Isaac Asimov. This is a short-story collection that includes the first appearance of the famous Three Laws of Robotics. Robots are a major theme in SF, and this is the robot bible.

The Martian Chronicles, Fahrenheit 451, R is for Rocket, I Sing the Body Electric, all by Ray Bradbury. Bradbury is widely respected even outside the genre for the nostalgic, melancholy quality of his prose, though some have criticized it as syrupy. (I disagree.) The Martian Chronicles is one of the earliest and most important books in the SF tradition of mythologizing Mars. Fahrenheit 451 is a major dystopian novel, and the other books listed are short story collections that include some widely anthologized works.

Childhood’s End, Rendezvous with Rama and The Collected Stories of Arthur C. Clarke, by Arthur C. Clarke. The first is an early novel about human transcendence; the second, one of the first novels featuring a BDO (Big Dumb Object, a cosmic MacGuffin); the third is a very comprehensive collection of Clarke’s short stories.

Starship Troopers, The Puppet Masters and Stranger in a Strange Land by Robert A. Heinlein. I don’t care for Heinlein much myself, but there’s no denying his influence. Three very different treatments of human contact with alien life, from the insidious to the benign.

Slan, by A.E. Van Vogt. This is one of the first treatments of the superhuman in SF. Canadian author.

The Stars My Destination and The Demolished Man by Alfred Bester. The first novel is about teleportation; the second, telepathy. These two books established many of the conventions of these particular themes.

1984, by George Orwell. Yes, this is SF; Oceana's iron-fisted control of its people would be impossible without speculative advances in technology (telescreens, anyone?). One of the major dystopias.

Brave New World, by Alduous Huxley. Another important dystopia.

Solaris, by Stanislaw Lem. A living planet and ordinary people in space. Lem's Futurological Congress is also important, and one of the prototypical SF satires.

The Forever War, by Joe Haldeman. Military SF through the lens of the Vietnam War.

Dangerous Visions, edited by Harlan Ellison. Probably the most important anthology of the New Wave movement, which hit SF in the late 60s.

The Beast that Shouted Love at the Heart of the World and The Essential Ellison, by Harlan Ellison. SF’s most respected (and controversial) writer of short stories.

The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed, by Ursula K. LeGuin. Sexual and interplanetary politics.

Flowers for Algernon, by Daniel Keyes. This could be the most personal of all SF novels, focussing as it does on the effect of a dangerous experiment on a single human being, told from that individual’s point of view. Some critics prefer the short story the longer work is based upon.

The Science Fiction Hall of Fame Volume One, 1929-1964, edited by Robert Silverberg. A must-have collection of the genre’s most influential short stories, up to the time of publication. Recently back in print.

The Science Fiction Hall of Fame Volume Two A/Two B: The Greatest Science Fiction Novellas of All Time, edited by Ben Bova. Same as above, but with novellas rather than short stories.

Dying Inside, by Robert Silverberg. Perhaps the best novel since The Demolished Man on the implications of telepathic powers, in this case their effect on a university professor who finds he is beginning to lose them.

The Man in the High Castle and Valis, by Philip K. Dick. An important alternate history, and a psychedelic, postmodern romp about the true nature of reality.

Dune, by Frank Herbert. Drugs, family drama and transcendence on a world of sand.

Way Station, by Clifford D. Simak. The downside of immortality.

Stand on Zanzibar, by John Brunner. An important novel on the threat and implications of overpopulation.

334 and Camp Concentration, by Thomas M. Disch. Two novels that focus on the social and economic pressures that conspire to make us less than human.

Slaughterhouse-Five, by Kurt Vonnegut. Time travel as a means of examining the horrors of the human condition.

A Wrinkle in Time, by Madeline L’Engle. Well-crafted kid-lit SF exploring themes of otherworldly possession and tesseracts.

Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang, by Kate Wilhelm. Major novel about human cloning and environmental catastrophe.

Berserker, by Fred Saberhagen. Robotic, self-perpetuating death machines scour the galaxy, wiping out all life forms. Only the similarly warlike human species has a hope of brining the Berserker rampage to an end. Important for its treatment of artificial intelligence, and the implications thereof.

More Than Human and To Marry Medusa (also published as The Cosmic Rape), by Theodore Sturgeon. Two great novels about humanity’s future as a gestalt being. To Marry Medusa in particular had a profound effect on me, because it showed that even the most loathsome specimen of humanity has something important to contribute to the welfare of the species.

Her Smoke Rose Up Forever, by James Tiptree, Jr. (Alice Sheldon). Short story collection by a female author who wrote very successfully as a man for most of her career.

The Dream Master and Damnation Alley, by Roger Zelazny. A novel on the nature of reality, another describing a post apocalyptic future.

Moving on down the line to some late-period SF:

Blood Music, by Greg Bear. The first novel to tackle, at least tangentially, the topic of nanotechnology.

Timescape, by Gregory Benford. A later time-travel novel – late enough to examine the implications of time travel technology more seriously, and with more basis in reality, than earlier examples of the form.

Ender’s Game, by Orson Scott Card. A wildly popular coming-of-age/alien invasion novel. Criticized in some quarters for its glorification of violence and dismissal of the quality of mercy.

The Handmaid’s Tale, by Margaret Atwood. A respected mainstream author writes an SF novel (though she denies that categorization). Another powerful dystopia, this time from a female perspective.

Doomsday Book and To Say Nothing of the Dog, by Connie Willis. Willis is one of the most respected and award-winning SF writers of the 80s and 90s, and she's in top form here.

Beggars in Spain, by Nancy Kress. A story about obligation told through the lens of an emerging race of human superbeings.

A Fire Upon the Deep and A Deepness in the Sky by Vernor Vinge. Complex novels about the nature of intelligence and the so-called technological singularity, one of the more recent “big ideas” in SF.

Red Mars, Green Mars, and Blue Mars, by Kim Stanley Robinson. “Hard” SF treatment of the terraforming of Mars, and the scientific and social implications of same.

The Speed of Dark, by Elizabeth Moon. A great thematic follow-up to Flowers for Algernon, this time about an autistic man who is presented with the opportunity to become “normal.”

I'm not as familiar with the fantasy genre as I am with science fiction, but here are a few of the milestones:

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis. If you can get past none-too-subtle Christian allegory, Lewis' tale of childhood wonder and its sequels are essential reading. An excellent example of one of the genre's most important themes: ordinary people thrust into an extraordinary world.

The Mists of Avalon, by Marion Zimmer Bradley. The Arthurian legend told from the perspective of the female characters in the tale.

Silverlock, by John Myers Myers. The hero is torn from his mundane life into the Commonwealth of Letters, where he encounters the settings and characters of many major works of literature.

The Lord of the Rings trilogy, by J.R.R. Tolkien. Everything in fantasy supposedly goes back to this, but I haven’t read it..!

Tigana, by Guy Gavriel Kay. Canadian author, writer of superior late-period fantasy.

Nobody’s Son and The Night Watch, by Sean Stewart. Two sentimental favourites by an Edmonton author. Nobody's Son is particularly charming; it explores what happens after "happily ever after," and it's a story well worth exploring by anyone who enjoys seeing a timeless formula turned on its head.

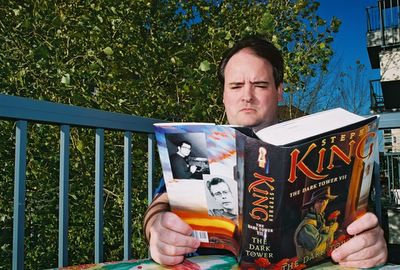

The Dark Tower series, by Stephen King. Part western, part SF, part fantasy, part metafiction. Peters out toward the end, but the early going is pretty amazing.

Tarzan of the Apes, by Edgar Rice Burroughs. Tarzan, Mickey Mouse, and Superman have been called the three most widely recognized icons of popular culture in modern history. After reading Tarzan, it's easy to see why the story remains powerful; it's a mythic tale of man's relationship with nature, his primal self, and the corrupting influence of civilization. In Burroughs' mythology, life as a savage is far from nasty, brutal, and short; it's a romantic wonderland of adventure, carefree sex, and the epic struggle of good versus evil, in all its various and sundry forms.

The definitive SF canon hasn't yet been determined; the genre, barely a century old, is still too young to properly evaluate. But I hope that the works I've listed will give interested readers a place to start exploring.

12 comments:

"Asimov was a hack."

A little off-track from your list, in that its focus is very narrow: Lawrence Sutin's "Divine Invasion" is a non-fiction biography of Philip K. Dick, or at least as non-fiction as a PKD bio could possibly get. It also represents to my mind one of the best-written examples of the form of contemporary biography in general.

Also needing mention on your list in the classical-classics department of fantasy: the Epic of Gilgamesh, Beowulf, and perhaps Homer's Odyssey. If you're going to build an edifice, you always start with the cornerstones.

Glad to see The Left Hand of Darkness on your list Earl.

Nor can I believe you haven't read The Lord of the Rings. Really, it's required reading, just as reference material. You can skip all the songy bits and not miss anything.

The only thing this post is missing is a picture of a "Speculative Fiction CANNON" that shoots out some of the books you mentioned.

I'm going to guess that the "Asimov was a hack" comment was Pete, but it's possible there are other Asimov unfans (maybe even plus-unfans or even double-plus-unfans) out there.

Nothing by William Gibson?

I'd say for the fantasy one, probably "The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant the Unbeliever" -- at least the first ones. Donaldson deals with some pretty weighty issues and shows ugliness as ugly.

Probably some Michael Moorcock too, just so that it's not all epic fantasy.

I agree with Anonymous the Third; Gibson should be represented and my vote is for "Neuromancer". A real departure from other sf of the time, generally regarded as the first 'cyberpunk' novel, and Canadian to boot!

An excellent list otherwise, and yes, for heaven's sake, read LOTR so your fantasy list has some gorram credibility.

- Stephen

I am feeling quite old enough today. Anonymous #1 has never been a Pete. The reference is to an inside joke that I believe will turn twenty years old sometime next year. If you didn't get it then, you won't get it now.

Well, let's add to the list some. The other day, I was buying gas for the car, and the attendant was reading a dog-eared copy of "Lord Of The Flies" (by choice!), written by William Golding. It's not exactly science fiction, although it has one off-hand mention of futuristic transportation technology - the airplane that crashes (not really a spoiler) - but it is one of those books that high shool English classes never escape from, nor should they. I actually quite loathe the book, but it does have a lot of social value in terms of what kind of power a book can have in modern culture, and love it or hate it, it deserves to be read, preferably under coersion, as in part of a windowless, cement-walled high school curriculum -- that, and "A Separate Peace". I digress.

Also kind of in the same category: the triumvirate of John Wyndham - The Midwich Cuckoos, The Chrysalids, and The Day Of The Triffids, each one better than the one before. Again, that's not to say I personally enjoyed these books, but they do represent a way that's gone past of recounting science-based narrative without indulging in the flash of space opera, or the lugubriousness of fantasy. Best enjoyed as part of a somewhat enlightened, yet strict and unliberated English Lit high school or early University class.

Gibson? Gibson. A nice enough guy, has a slick way with words, but ends up no better than a cyber-soap opera regarding plot and character. Students will be drawn to the pre-Matrix "Johnny Mnemonic" movie with the unfortunate Keanu, and will be scarred for life. Beware of Gibson, it's dated, and fraught with pitfalls, but if you know what you like, I guess he's an enjoyable read, certainly memorable for patches of vivid descriptive writing.

Lastly, by all means read your Tolkein. Good, straightforward fantasy that sets a standard for a lot of stuff that has to follow. Too bad Tolkein a) couldn't self-edit, b) find endings to big story arcs, or c) write women, otherwise he's be in the same league as the true contemporary giant of genre fiction: Patrick O'Brian. Trouble is, Patrick O'Brian mostly wrote novels about the Napoleonic Wars, which isn't quite the genre you are interested in, Earl. Still, anybody who enjoys reading at all owes it to themselves to give O'Brian a chance.

Thanks for the excellent feedback, everyone. As I suspected, I missed some important stuff - but in the process I received some valuable insights!

P.S. I remember the "Asimov was a hack" reference - the time frame and the words, if not the exact circumstances. Who was taunting whom that time?

Hmmm, I don't remember anyone getting taunted, I just remember it as one of those things that gets blurted out by way of mouth before the brain has a chance to say to it, "Shut up, you!" In sermo inconsideratus adveho verum.

Still, I wouldn't consider myself one of Asimov's fans. He was definitely a brilliant scientist who could also write moral plays, and his best work is the kind of stuff that you can think about much later, rather than as you are reading it. On the other hand, not very much of his writing has colour or excitement to it, and one futuristic vista (or character)in an Asimov novel is fully interchangeable at any time with at least a dozen others. That makes his writing actually pretty easy for the novice to get into, and maddening for someone who decided to slog though any great percentage of his many, many stories.

Post a Comment