You Seem Wise, for a Woman: Gender Roles in Star Trek's "Who Mourns for Adonais?"

Star Trek has been praised for its progressive vision of an egalitarian future, where men and women of all cultures work together for the greater good.

Star Trek has also been derided for advocating everything from communism to imperialism – and for its sexist attitudes. The show’s central figure, Captain James T. Kirk, is commonly regarded as an intergalactic Lothario, with a woman in every starport.

There is ample evidence for both views. If one examines the Star Trek canon, one discovers that the show is both progressive and reactionary – and often in the same episode. “Who Mourns for Adonais?”, the second broadcast episode of the show’s second season, is one such episode.

What’s in a Name?

Adonais, it should be noted, is a corruption of Adonai, one of the Hebrew names of God – fitting, since this episode deals with the downfall of a god, namely Apollo. The name Adonis, a Syrian god of death and rebirth incorporated into Greek mythology, can also be traced back to the Semitic term; Adonis was, according to a fragment of the poet Sappho, the central figure in a cult formed by the young women of the isle of Lesbos. The Lesbians worshipped Adonis, and sowed herbs and grains during a festival dedicated to him – and then mourned when the plants died, grieving not only for the vegetation, but also for the god who represented the cycle of death and rebirth.

According to Walter Burkert’s text Greek Religion,

“…the special function of the Adonis cult is as an opportunity for the unbridled expression of emotion in the strictly circumscribed life of women, in contrast to the rigid order of polis…”

Adonis worship, then, was liberating – and sexual. Even today, to call a man an Adonis is to complement him on his godly physique; he is put upon a pedestal, and becomes both an object of worship and desire. An Adonis, then, could be said to be playing two roles: ruler, and prey.

Adonis does not appear in the episode, but the show’s antagonist, Apollo, certainly plays the role of the classical Adonis.

Kirk and McCoy wonder if Mr. Scott is wise to pursue Lieutenant Palamas.

Losing an Officer

As the episode opens, we learn that the Enterprise is en route to investigate Pollux IV, an M-class (Earthlike) planet of little note. (Pollux, of course, is another son of Zeus, a stepbrother to Apollo.) On the Enterprise bridge, Captain Kirk receives a report from Lieutenant Carolyn Palamas, an attractive young officer who we learn is the ship’s “A&A” specialist: archeology, anthropology, and ancient civilizations. The ship’s engineer, Mr. Scott, is quite smitten with Palamas; he asks her out for a cup of coffee. Kirk and ship’s doctor Leonard McCoy look on, amused:

“Bones…could you get that excited over a cup of coffee?”

“Well, even from here, I can tell his pulse rate’s up.”

Palamas and Scott exchange a few words; clearly, Scott is love struck, an avid pursuer of the friendly but aloof Palamas. Kirk and McCoy worry:

“I’m not sure I like that, Jim.”

“Why? Scotty’s a good man.”

“And he thinks he’s the right man for her. But I’m not sure she thinks he’s the right man.”

At first glance, this seems to be an affirmation of a woman’s right to choose her mate. But McCoy goes on:

“On the other hand, she’s a woman. All woman. One of these days she’ll find the right man, off she’ll go – out of the service.”

Clearly, the assumption here is that should a female Starfleet officer become romantically entangled, she’s expected, by cultural norm if not by law, to surrender her career and, by implication, take on the role of wife and mother. Kirk responds:

“I like to think of it not so much as losing an officer, but gaining…actually, I’m losing an officer.”

Interestingly, here Kirk regards Palamas primarily as a colleague, and a valuable one; he sees no upside to her taking on the role of housewife. But before McCoy can respond, trouble: a giant green hand appears outside the ship, taking hold of the hull and stopping the Enterprise in its tracks.

Grabbed by the hand of Apollo, the crew is once more flung across the bridge.

Apollo’s Vision

Baffled by the apparition, the Enterprise crew quickly brings to bear their scientific apparatus in an attempt to explain the phenomenon. The hand is actually a force field, though an exotic one, and it’s holding the ship in orbit around Pollux IV.

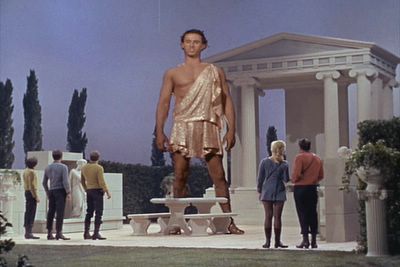

Then, another apparition appears on the ship’s viewscreen: the face of the Greek god Apollo, clad in a toga and laurel wreath. He welcomes the children of Earth, and informs them that they shall worship at the feet of Apollo, just as their ancestors did so long ago.

Naturally, Captain Kirk has other plans.

In the Temple of Apollo

Kirk, McCoy, Scott, Ensign Chekov, and Lieutenant Palamas beam down to the surface of Pollux IV. Palamas wonders why she was included in the landing party, and McCoy informs her that her specialized knowledge of classical civilization could come in handy on this mission. This is a little insulting to Palamas’ character; surely she could have figured out for herself that her specialty could be useful in dealing with a Greek god. This instance, however, is probably not so much overt sexism on the part of the writers (or McCoy); it is simply exposition, a way to explain to the audience why Palamas is involved in the plot. Still, the text is the text, and if we accept it at face value, Palamas, at the very least, comes across as an officer who pays little attention to current events aboard ship, calling her competence into question.

“I am Apollo!” shouts the god, by way of greeting.

The men of the landing party are skeptical:

“And I am the Czar of all the Russias!” says Chekov.

“Chekov…” Kirk chides.

“I’m sorry, sir, I’ve never met a god before.”

“And you haven’t yet.”

The god and his potential flock.

Palamas, on the other hand, is clearly enthralled by Apollo’s presence; he is powerful, handsome, an Alpha male in all respects. And he isn’t above using flattery to sway the lieutenant:

“Earth…mother of the most beautiful women in the universe…that, at least, has not changed.”

Earth itself is characterized as female by Apollo, and we can infer that to him, womanhood’s chief virtues are beauty and motherhood. He will make his attitudes explicit soon enough.

Apollo makes a dramatic exit, leaving the humans to confer for a moment. Kirk asks Palamas what she knows about the god, and her reply is concise and professional:

“…twin brother of Artemis, son of Zeus and Leto, god of light and purity, skilled in the bow and the lyre…”

Apollo returns, demanding that Kirk and his crew worship him. Kirk is indignant, and starts to make a threat of his own:

“I have four hundred people up there…”

“I have four hundred people,” says Apollo, “they are mine, to cherish or destroy.”

Palamas immediately steps forward to plead with Apollo, imploring him to be kind.

“How like Aphrodite and Athena…beauty…grace…You seem wise, for a woman.”

Apollo compliments Palamas’ physical attributes, and seems genuinely surprised by her intelligence – a sexist attitude if ever there was.

“What is your name?” he asks.

“Lieutenant Palamas,” she responds, using her professional title.

“I mean your name,” Apollo says dismissively. Clearly, he is unimpressed by her rank, which also implies he is equally unimpressed with any of her career accomplishments. To Apollo, a woman is to be cared for, admired, loved – but not treated as an equal.

Lieutenant Palamas' new look.

“Carolyn,” Palamas admits, and Apollo smiles warmly, then promptly uses his power to transform the lieutenant’s Starfleet uniform into one of William Ware Theiss’ infamously skimpy costumes. Rather than recoil at the indignity, Palamas actually preens, looking down in wonder at the dress.

Scotty pays the price for his jealousy.

Scott is rather nonplussed by all of this, and attacks Apollo, only to be struck down with casual ease. As the men tend to the injured Scott, Apollo takes Palamas to another dimension, a wooded glade where they can talk in private. Scott, though winded by the rough treatment, is eager to go after them, but Kirk holds him back:

“I understand your concern over her, Mr. Scott, but she volunteered to go with him, hopefully to learn something about him. She’s doing her job, and it’s about time you did yours.”

Kirk’s statement reveals his contradictory feelings about Palamas, and perhaps by extension, all female Starfleet officers. He uses her as an example of proper behaviour for Scott; but on the other hand, he is merely hopeful that she’s gathering intelligence on the god, rather than pursuing her obvious infatuation with him.

In the garden with a god.

Meanwhile, Back on the Enterprise

In orbit, the Enterprise is still helpless, her engines useless, communications, transporters and sensors inoperable. Mr. Spock cannot contact the landing party, nor retrieve them, nor even gather data on their condition. The ship is blind and impotent. Mr. Spock confers with Lieutenant Uhura, the communications officer, a woman.

“Lieutenant, we must restore communications with the landing party.”

“Well, I’m working, sir, but I can’t do anything with this,” she says, indicating her inoperative communications control panel.

“Oh?”

Uhura reconsiders.

“Well, I might be able to rig up the subspace bypass circuit…”

“Good, do so.”

Spock moves on to another station, clearly confident that Uhura will make the necessary repairs. Spock, of course, is well-known in popular culture as a character motivated only by cold logic; emotions do not factor into his decisions or attitudes. Unlike Kirk, Spock’s estimation of character is based on experience; the captain relies on intuition. Shortly, Spock checks on Uhura’s progress:

Uhura, consumate professional.

“I’m connecting the circuit now, sir. It should take another half hour.”

“Speed is essential, Lieutenant.”

“Mr. Spock, I haven’t done anything like this in years…if it isn’t done just right, I could blow the entire communications system. It’s very delicate work, sir.”

“I can think of no one better equipped to handle it, Miss Uhura. Please proceed.”

Foiled by Feminine Virtues

On the planet, the male members of the landing party have a plan to defeat Apollo: using their tricorders (portable sensory equipment), they have determined that whenever he uses one of his godly powers, his energy levels drop. If they can taunt the god into expending enough energy, perhaps the Enterprise will be able to break free of Apollo’s weakened grip. A dangerous plan, Kirk admits, because Apollo’s wrath could easily kill the entire landing party before the Enterprise can take action. But it’s a risk they’ll have to take.

Apollo and Palamas return from their idyllic paradise, and Kirk readies the men:

“Look out for the girl,” he admonishes. Out of uniform, Palamas is no longer an officer, but merely a woman – rather, merely a girl, a figure to be protected, or perhaps an irritant to be dealt with. The men begin to taunt Apollo, and the god is wrathful indeed; Kirk knows that his plan will work.

But then Palamas, not aware of the plan and terrified that Apollo will strike her friends dead, intervenes, begging the god for mercy. Apollo relents, and Kirk is appalled, exasperated; she’s ruined the plan, and they’ll have to come up with another. Palamas’ compassion – a quality traditionally associated with women – has botched Kirk’s plan.

"Wonderful...just great. Thanks for nothing, Lieutenant."

A Tempting Offer

Once more, Apollo and Palamas retire to the otherworldly garden, and Apollo makes an astonishing offer: he will make Carolyn his bride, and furthermore, the mother to a new race of gods, to be one day be revered almost – almost – a goddess herself. Palamas is good enough to serve as Apollo’s consort, and as a mother, but she will not be elevated to equal status with Apollo himself.

Palamas’ Predicament

Kirk has one final plan, and it depends upon Palamas’ loyalty. But as soon as Palamas returns from the garden, awestruck, she tries to convert Kirk:

“He wants us to live in peace. He wants to provide for us. He’ll give us everything we’ve ever wanted…”

Kirk’s response is harsh, and designed to appeal not to Carolyn the woman, but Palamas the officer:

“All right, Lieutenant, you can come down from Mount Olympus now. You’ve got work to do. [Apollo] thrives on love, worship, attention. We can’t give him that worship. None of us can, especially you. Spurn him. You must. You’re special to him.”

“Yes…I love him.”

“Lieutenant. All our lives, here and on the ship, depend on you. On you, Lieutenant. Reject him, and we have a chance to save ourselves. Accept him, and you condemn all of us to slavery.”

Palamas doesn’t like the sound of this.

“What you ask would break his heart. How can I?”

"Man or woman, it makes no difference. We're human."

“Give me your hand,” Kirk demands, and she does. “Now feel that. Human flesh against human flesh. We’re the same. We share the same history, the same heritage…man or woman, it makes no difference. We’re human. We couldn’t escape from each other even if we wanted to.”

In contrast to his earlier, more patronizing attitude, here Kirk rediscovers his earlier respect for Palamas as a human being (“…actually, I’ll be losing an officer.”). Kirk never calls Palamas by name; he refers to her by her rank, reinforcing her status as a valued crewmember. On the other hand, by doing so he is subverting her female response to the god – to Adonis. He knows that an Adonis’ greatest weakness is to be wounded by a woman’s rejection. Kirk is using Palamas’ femininity as a weapon.

"It's not me, it's you." Welcome to dumpsville, population: one angry Greek god.

Palamas rejoins Apollo in the garden. She denies her feelings for the god, calling him a specimen, an experiment. She calls herself a scientist.

“Surely you know I’ve only been studying you. I could no more love you than I could love a new species of bacteria.”

Apollo is devastated, and enraged, he threatens Palamas, and her demeanor shifts: while it hurt her to betray Apollo, his sudden belligerence seems to awaken her own feminist impulses. Her face a mask of scorn, she confronts him:

“Is this the secret of your power over women? The thunderbolts you throw?”

Apollo, the very picture of a petulant male, raises his arms to the sky and brings down a storm, forcing Palamas to flee.

Apollo’s Fall

Uhura’s repairs, now complete, enable Spock to reestablish contact with Captain Kirk, and Apollo’s temper tantrum has drained just enough energy for the Enterprise to act. Spock warns Kirk to stay well clear of Apollo’s temple, for it is his power source, and the Enterprise is about to destroy it.

A technological thunderbolt: Enterprise phasers destroy Apollo's temple.

The starship’s weapons raze the temple, and Apollo’s power is gone. But he does not rage against Captain Kirk: instead, he casts his mournful gaze upon Palamas, who stumbles from the garden into the arms of Mr. Scott; unable to keep her own footing, she is dependent upon yet another male for support.

"See what you've done to me."

“See what you’ve done to me,” he tells her, and tears stream down his cheeks. Apollo calls out to the other Greek gods, who long ago allowed their essences to disperse into the cosmos. He spreads his arms wide and disappears, willing himself to death.

Palamas, too, is crying, though the cause is open to interpretation: does she cry because of her betrayal? For the ordeal she’s just been through? Or because a unique life-form has been lost?

Who Mourns..?

Who mourns for Adonais? As Burkert noted, it is women who grieve for their lost god – and certainly Carolyn Palamas follows this pattern. But the men of the starship Enterprise mourn as well:

“I wish we hadn’t had to do this,” McCoy says.

“Would it have hurt us, I wonder,” laments Kirk, “to gather just a few laurel leaves?” In the end, man and woman are on a level playing field: together, they have defeated God, and together they mourn. But is this a meaningful measure of equality?

Death of a god.

Carolyn’s Choice

Captain Kirk is a man very much in the Dionysian mold: he tries to seduce, or at the very least admires, nearly every female guest star in the series. Kirk’s attitudes towards women, then, may or may not be typical of twenty-third century males. However, as the lead character, Kirk’s is the voice that most informs the fictional world of the series; it is his actions and attitudes that propel the narrative.

But his subordinate, the half-human, half-alien Mr. Spock, is at least as important to the show as the captain, if not more so; certainly his hold on popular culture is as strong or stronger than Kirk’s. And Spock’s attitude towards women, in this episode and others, is unfailingly respectful, even on those rare occasions when he feels a romantic pull towards the female in question.

Scotty comforts Palamas...but her mind is on other things.

Mr. Scott’s role in the episode is also worth examining. Throughout, he behaves like a lovesick teenager, moved wholly by emotion (primarily jealousy and anger), to the detriment of his own health and even the starship’s mission. And in the end, though he is allowed to comfort his beloved Carolyn, we know the romance he desires will never come to fruition: the Palamas character never reappears on the show. Mr. Scott failed to treat Palamas as an officer, and Palamas, we may infer, responds with indifference to his romantic attentions. And it is difficult to blame her.

At story’s end Palamas rejects both the love of a god and the love of an ordinary mortal: she makes her own choices. Does she, as Kirk and McCoy surmise, eventually find a man and leave the service? We never find out. Certainly she wanted to experience the love of a man, and expressed submissive tendencies – but only to Apollo, a god, never to the mortal Scotty. She is clearly confident in her abilities as an officer and a scientist.

We cannot know what path Carolyn Palamas chooses after the episode fades out. But we do know that when the moment of decision came, she rejected a submissive role and reclaimed the right to live as an independent actor, whatever the consequences. Her final choice is an affirmation of her importance as a human being.

“Man or woman, it makes no difference. We’re the same. We’re human.”

Despite inconsistencies in the text, this is Star Trek’s ultimate message. Men and women are, above all else, human, sharing the same rights and responsibilities, the same frailties, the same potential. We can, like Scotty, submit to our baser emotions, or we can, like Palamas, rise above them. Our capability to do so rests not with our gender, but according to our own strength of character.

Hi Earl! Great close reading of the episode -- I don't think I've ever seen this one (or it's lost in the dust of my adolescent mind). I wonder about Kirk's sexual behaviour. Although he's given to us through the trope of ladies' man, a cultural shorthand that makes understanding him easy for contemporary audiences, perhaps his free sexuality indicates more about the way the writers imagined sexual relationships in the twenty-third century.

ReplyDeleteThat said, a feminist could read the call for balance in the exhortation "We're human" as an indictment of the growing feminist cause in the 60s. Although we might like to believe that enlightenment on one front leads to overall enlightenment, I don't think this is necessarily true (see the testimony -- can I really use that term in this context? ugh -- of many women members of the anti-Vietnam movement, the civil rights movement, the Beat generation, the punk underground, etc., etc.).

Do more of this! I really enjoyed this essay.

L

Thanks for the feedback, Leslie! In truth, I've always been rather forgiving of Kirk's amorous tendencies for the very reason you offer: I tend to think that sexual attitudes would be much more relaxed in the future. (It certainly seems that way if you read Gene Roddenberry's novelization of the first Star Trek movie - perhaps I'll explore that subject someday.)

ReplyDeleteAs for Kirk's "We're human," line, it does come off as a rebuke in the episode, so you could have a point - though my own subjective (and perhaps wishful) interpretation is that Kirk is truly experiencing a moment of genuine egalitarian impulse.

Apollo takes a seat in the temple. "You will learn discipline. You will learn..." Cut to Chekov, his eyes dropping from Apollo's face to...to what? Apollo's voice trails off as his eyes lower, following Chekov's gaze. He realizes the young navigator is staring directly at his exposed crotch. Mortified, the god quickly vanishes. (28m)

ReplyDeleteI'm pretty sure that scene wound up on the cutting room, floor, Allan. Too bad!

ReplyDeleteThanks for the comment, Susan. King's comment that "this is not a black role, this is not a female role" was very insightful, and must have resonated through the years, for later Trek series often tested actors of different races and cultures for different roles; the captain of Deep Space Nine, for example for which they tested black and white actors, and Voyager, for which they tested men and women (although in that case, they were hoping to try a female captain)>

You and your science fiction. Oh, sure, it looks like it's all about the flashy lights and the shooting lasers, but they always try to stick a lesson or two about social justice in there. That's like fortifying Coco Puffs with vitamin C. I feel so used.

ReplyDeleteUh, no Earl, that scene is most definitely in the episode. At the 28 minute mark, as a matter of fact. Go check.

ReplyDeleteI did enjoy your analysis, btw, even if you missed the obvious intentional homoerotic overtones.

Well, now I'm going to have to go and check.

ReplyDeleteDid you check?

ReplyDelete